What are the top 10 trends for the next ten years? Download the report here.

Are you guilty of being a “doer” or “fixer”? I sure am. Tell me you’re hungry within an earshot and I will immediately think about what to do about it. Being able to just listen and acknowledge is just as important, but the problem solver in me is a deeply ingrained part of how my mind works.

That might be why one of my favorite parts of the foresight process is the shift from creating scenarios to actually using them, from exploring alternative futures to deciding what should happen to pursue a preferred future. After asking “What could happen?” it’s now “What are you going to do about it?”

The answers in this new phase are strategies that are “crossover levers” — meaning, they make sense in multiple futures, increase your resilience, and help you not just survive but thrive in a range of circumstances.

What’s a lever in foresight?

In the futures process, a “lever” in a story or scenario is:

- A factor that you can control or influence.

- Like a dial on a radio. You can turn up your response and be proactive or you can turn down your response and be mute.

- A thing that will influence the severity or impact of disruptions on your future.

The specific lever depends on whose perspective you’re using (i.e., you, your organization, your community).

For instance, you may be seeing increasingly severe and/or frequent extreme weather now and even more so in the future. Of course, you can’t control or influence weather patterns, so that’s not a lever. However, you can influence or even control to some degree what people do to prepare for weather-related emergencies — that’s a lever. In this case, the lever could be articulated as “increasing the capability of my loved ones/residents/clients/members to anticipate and recover from weather-related emergencies.”

As this example illustrates, levers may focus on preventing, reducing, or avoiding negative outcomes, and on doing well despite challenging forces or circumstances. Levers may also focus on assuring or even accelerating positive developments. For example — in a story describing successful grassroots efforts that increase voter turnout, a lever might be to identify and support such activities today.

What about levers to address forces that function like double-edged swords? Such forces include:

- Advances in social media that facilitate as well as harm our sense of connection and community; and

- Applications of artificial intelligence that improve services as well as put people out of work.

In situations like these, levers don’t have to focus on stopping or accelerating the trend itself but rather focus on mediating its impacts, and minimizing harm while supporting benefits. Levers dealing with the two examples above may include:

- Helping users learn and apply practices that help them use social media in ways that protect their privacy and increase their mental health; and

- Using automation to improve job satisfaction and offering job training opportunities for displaced workers.

When a lever helps you thrive in multiple futures across different circumstances, then you have what’s called a “crossover lever” — a type of strategy that is robust and supports your resilience. Once you have a list of crossover levers, you can unpack and translate them into action-oriented and collaborative plans using an approach like Strategic Doing.

How can I identify such levers?

I recommend using this approach:

- Review one story or scenario and assume it comes true as described.

If it helps, wear a different outfit while reading each story, sit in a different location, listen to a different background tune — whatever helps you “step into” that future and temporarily accept it as reality.

Also, if you’re the (co-)author of one of the scenarios, read and analyze your own scenario last.

- Write down as many levers as you can for that scenario. What would you or your organization or your community do in that future, to survive and even thrive?

Articulate levers in the following way: [verb] + [factor]. For example, “affordable housing” is a popular problem to solve in communities across the world, but it’s not a lever. If you have any influence or control over supply, your lever might be to “increase affordable housing options.” You can also get more specific than that, such as to “increase affordable housing options for residents earning up to $25,000 per year.” If you work in consumer financial services, your lever is going to look a little different — for example, to“increase equitable access to home loans.” If you’re a health care professional, a lever might be to “direct low-income patients who suffer from health conditions exacerbated by poor housing to a trusted partner who can assist them.”

1/11/21 Edit: In their book, How to Future: Leading and Sense-making in an Age of Hyperchange (2020), Smith and Ashby offer a range of questions you may also find helpful in this step. Here are some: What kind of talent or skills would be needed to get the most out of this scenario or minimize the risk presented by it? What kind of information, data, insights or experience would this scenario require? What technology, processes, platforms or other kinds of tools would this scenario require? What regulations, frameworks, rule sets or other guiding frameworks would this scenario require? What partnerships, ecosystems or alliances would this scenario require?

- Repeat with the next scenario, creating a separate list of levers for each scenario.

- After you have a list of levers for each scenario, look across these lists for shared levers or themes and articulate those groupings.

What does it look like with four scenarios?

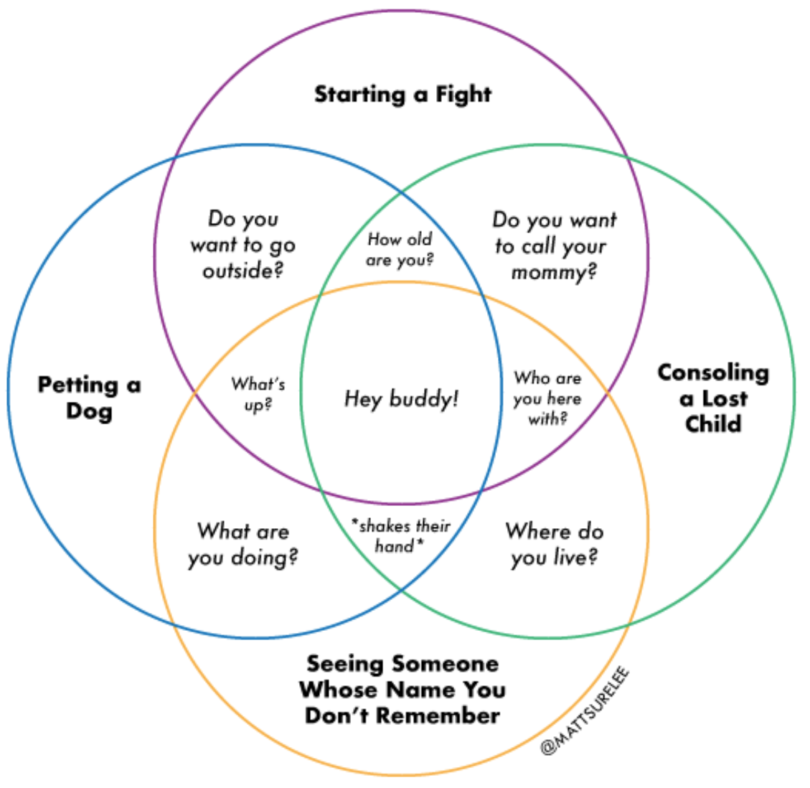

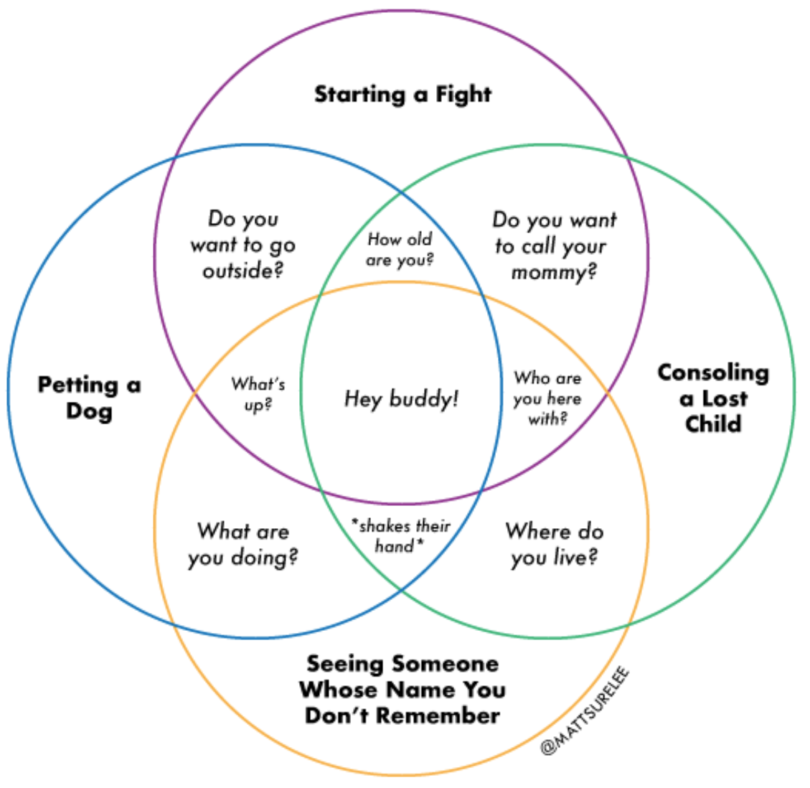

Let’s demonstrate levers with a set of mini-scenarios. The Venn diagram at the top of this article compares four different scenarios: a bank robbery, church service, dance club, and a parent helping a child take off a sweater. Here is the visual again for your reference:

There are a range of possible actions within any one of these scenarios, but the overlaps between scenarios are shared levers. This diagram focuses on a particular type of lever — you can control or influence what you say or the instructions you give.

For example, imagine you are a DJ at a dance party or a robber inside a bank. Saying “everyone on the floor” makes sense in either circumstance. You can decide on the volume, frequency, and timing of this instruction; and it helps you influence the outcome. So “tell everyone to get on the floor” is a shared lever. It alone is unlikely to guarantee your success, but it’s part of a package of useful actions to prioritize.

If you’re the preacher or the parent, telling everyone to “get on the floor” is a possibility, but it won’t assure the desired outcome in both situations. However, using explicit or implicit verbal threats could assist with this. So, “tell everyone that ‘if you don’t listen to me there will be severe consequences’” is the shared lever between these two scenarios. Presumably bank robbers don’t use this language verbatim, but the gist of this lever is also relevant to their aims. As such, a shared lever among all three scenarios could be to “convey how compliance is in their best interest” and/or to “convey how noncompliance has negative consequences.”

Continuing with this fun example, the equivalent of a crossover lever sits in the middle of the figure (i.e., “tell everyone to put their hands in the air”), because it makes sense to say in 3–4 of the scenarios and it would help you pursue a preferred future (“preferred” here is defined by whichever role you play). Another crossover lever that isn’t listed in the figure but is relevant to 3–4 scenarios is the one I suggested in the previous paragraph about compliance.

12/17/20 Edit: Check out the original meme with just three scenarios. And here is an even more elaborated version with five scenarios.

For a more serious application of crossover levers, you can check out the Public Health 2030 scenarios by the Institute for Alternative Futures. When you download that report and open it, you’ll see a list of strategy recommendations on pages 41 through 48. Those are beefy crossover levers to advance public health in the U.S. over the years to 2030, developed with the help of dozens of leaders and experts in public health. That report was published in 2014 and those levers continue to make a whole lot of sense.

The bigger picture

Using scenarios to identify crossover levers is valuable in more ways than one. Yes, you can use those levers to clarify, change, or affirm your strategic priorities. But what’s more, the broader process itself — exploring alternative futures and identifying crossover levers — enables you to integrate a variety of perspectives and build a community with a shared understanding and ownership of what the priorities are and why. The conversations you have internally and externally on strategy, tactics, and changes can be guided by the future (what’s coming), rather than solely the past (because this is how we’ve been doing it).

Guess who talks like that? Visionary leaders. But instead of limiting visionary leadership to one or the few at the top, it can become a broadly shared responsibility and practice. Now that’s a crossover lever.

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe to our newsletter.

Yasemin Arikan

Yasemin (Yas) Arikan operates the research vessel. She is a futurist who uses foresight and social science methods to help clients understand how the future could be different from today and then use these insights to inform strategy and vision. Her work includes developing scenarios on the futures of public health, health care, society and technology for associations, foundations, government, and business. Bonus: Yas can help you take your gift wrapping game to the next level. And she can talk with you about it in English, German, or Turkish. Watch Yas' Q&A on how NGC helps organizations prepare for the future using Strategic Foresight.

Yasemin Arikan Promoted to Director of Futures Research

NEXT Generation Consulting (NGC) announced the promotion of Yasemin Arikan to Director of Futures Research. Arikan will lead the company’s efforts to...

Is Your Housing Market Ready for Your Future?

One of the biggest problems facing many cities and towns is inadequate housing. This problem is most acute for seniors, veterans with disabilities, and low-income groups ...

Three Things Martha Stewart Gets Right About Return to Office (RTO)

The original influencer and the person who invented the "Home" retail category, Martha Stewart, became the latest CEO to tell employees to get back to the office five day...